The Native Plants and Native People Trail at the San Diego Botanic Garden teaches visitors how the Kumeyaay used local plants to survive and flourish.

Kumeyaay natives lived in the San Diego region long before Juan Cabrillo sailed his Spanish galleon into San Diego Bay. By 1542, the Kumeyaay were settled throughout San Diego County as well as Imperial Country to the east and Northern Baja to the south.

These Native Americans lived well in Southern California and they did so by utilizing the region’s natural resources. The Kumeyaay caught fish, hunted animals, collected shellfish and used native plants for medicine, food, drink and shelter.

In this article, we tell the story of how the Kumeyaay came to live in San Diego. We then describe the various plants these people used to stay nourished, to keep dry, to build tools and to cure ailments.

All of the plants discussed below can be seen growing along the Native Plant and Native People Trail at the San Diego Botanic Garden.

Located a few miles from the ocean in Encinitas, California, the San Diego Botanic Garden includes two natural plant communities within its grounds. The Garden sits on land that includes a mix of native plants from the Coastal Sage Scrub biome and the Southern Maritime Chaparral biome.

The Kumeyaay lived comfortably among both plant communities. The Native Plants and Native People Trail offers a window into the way of life for these San Diego natives.

Perched on the overlook tower, Lesley Randall, a botanist at the San Diego Botanic Garden, describes the plant communities below.

A recreation of a typical Kumeyaay settlement on display at the SDBG.

The Kumeyaay lived in dome shelters called ‘Ewaa.

A framework of willow branches were first bent into the dome structure. A thatch of lighter and broader plants (reeds, cattails) were then laid on top to keep out the sun and rain.

Early Kumeyaay history

Prior to 20,000 years ago, there were no humans living in North America – just plants, animals and microorganisms. That all changed when a group of Homo sapiens migrated out of northeastern Asia and across the Bering land bridge. These early humans found themselves at the top of North America, in modern day Alaska.

These Native Americans migrated and settled throughout North America. They chased herds of big game: woolly mammoth, mastodon, saber toothed tiger.

Eventually a group of natives wandered south and found themselves in the temperate Mediterranean climate of Southern California. Experts hypothesize human settlers arrived in the San Diego and Northern Baja region approximately 12,000 years ago. These early native settlers survived on the ample natural resources of the region: abalone, mussels, saltwater fish, deer, rabbit and a diverse selection of plants.

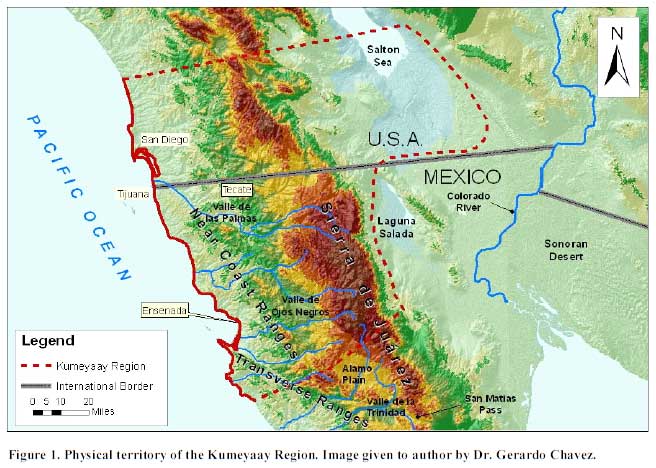

In time, a defined culture of Native Americans emerged in this region, the Kumeyaay. These people, also known as Tipai-Ipai, formerly called Diguenos, settled in a region that ran north to Oceanside and south to Ensenada, Mexico. From the Pacific Ocean, the Kumeyaay lived throughout modern day San Diego and Imperial Country – out to the the Salton Sea and the Colorado River. Estimates for the population of these people ranges from 3,000 to 15,000 people.

Kumeyaay family walks with dog and horse. An Opuntia cactus is seen on the right. Engraving published by Schott, Sorony, and Co., 1857.

photo: Michael Wilken

Range of traditional Kumeyaay territory.

Plant communities occupied by the Kumeyaay

Coastal scrub

The Kumeyaay had various settlements along the Pacific Ocean coastline. This biome includes large areas of coastal scrub and native grasslands. Today, this biome has been greatly reduced due to urbanization and development.

Chaparral

The area between the coast and the foothills of the Coast Range is covered with a shrubby, chaparral plant community.

Juniper-Oak-Pine woodlands

As the Kumeyaay settled in higher elevations along the coastal mountains, they found themselves among more evergreen trees. This biome includes present day Julian and the San Bernadino area.

Sonoran desert

Some Kumeyaay lived on the eastern side of the coast range. This area is incredibly dry as most of the precipitation falls on the western slope. The Sonoran biome contains true desert plants; cactus, palms, agave other drought tolerant plants.

Coastal sage scrub

Sonoran desert

Ethnobotany of the Kumeyaay

Ethnobotany is defined as the study of the interactions between people and plants.

For the Kumeyaay people, their entire existence hinged on their ability to utilize the plants of the region. Every facet of the Kumeyaay way of life (food, shelter, clothing, weapons, art) was intertwined with the local flora.

So…what were the regional plants that became integral to Kumeyaay culture?

Below, we’ve described some of the plants used by the Kumeyaay. As mentioned, each of these plants can be seen growing along the Native Plants and Native People Trail at the San Diego Botanic Garden.

Opuntia

photo: Rachel Cobb

Opuntia (Opuntia littoralis)

When gathering the fruits from this cactus species, the Kumeyaay would consume some of the fruit immediately, eating the pulp with or without seeds, or making it into a drink. Gatherers also processed both fruit and seed for later use, drying out the plant material in the sun. Dried seeds, or seeds and dried pulp together, were ground into meal and eaten as mush or flattened into cakes.

The Kumeyaay also ate the young cactus pads, fried or boiled.

The spines of this cactus were used to create tattoos.

Shaw’s agave

Shaw’s agave (Agave shawii)

Leaf fibers from this agave, also known as coast agave, were used to make shoes, clothing and rope.

The large flower stalks were roasted and eaten.

Del Mar manzanita

photo: Rachel Cobb

Del Mar manzanita (Arctostaphylos gladulosa spp. crassifolia)

The Del Mar manzanita is the rarest of the six recognized subspecies of Eastwood Manzanita, Arctostaphylos gladulosa. This rare plant is only found along bluffs in San Diego and parts of Northern Baja.

Throughout the Californias, native peoples used the fruit of this shrub to make a drink. Many Kumeyaay still gather the fruits for this purpose. The leaves were also made into a tonic for kidney ailments. This species is part of the Heather or Ericaceae family.

Yerba Santa

photo: Rachel Cobb

Yerba Santa (Eriodictyon trichocalyx or crassifolium)

Two species of yerba santa grow in regions of the coastal scrub, chaparral and mountain biomes of the Kumeyaay region. E. trichocalyx has darker, shiny, sometimes sticky leaves. E. crassifolium features lighter, felt-textured leaves. Both varieties have been employed medicinally, generally in similar ways. Throughout the Californias, native peoples used yerba santa for treating colds, sore throats and for general aches and pains. This Boraginaceae species was also highly regarded by the Spanish, who gave it the name of yerba santa (holy herb).

Surviving descendants of the Kumeyaay still use this plant for colds. A handful of leaves and stems are boiled in about three cups of water. The decoction is drunk three times a day while cold symptoms persist.

California live oak

California live oak (Quercus agrifolia)

This evergreen oak, also known as coast live oak, was considered the primary food source of the Kumeyaay. The Kumeyaay people would eat these acorns every day. Live oak acorns were gathered intensely in November and December. If there was a good harvest, the acorns might last for a year.

Tannins had to be leached from acorns prior to consumption. Tannins are natural, polyphenolic compounds that bind up with various amino acids and alkaloids. They bind up our salivary proteins when we eat them, which creates an undesirable sensation and makes our mouth pucker up. Banana peels also have tannins, which is part of the reason we don’t eat the peels.

The need to remove unwanted compounds from a wild plant prior to consumption is common among foraging societies.

The live oak acorns were also sometimes toasted and grinded into a powder, so as to make coffee.

Coastal scrub oak

photo: Rachel Cobb

Coastal scrub oak (Quercus dumosa)

California natives were not fond of the acorns from this oak species. Acorns from the live oak were much preferred. However, if coastal scrub oak was the only option, then natives would eat these acorns.

The Kumeyaay did appreciate the hard wood of the coastal scrub oak for firewood and construction material.

Toyon

photo: Stan Shebs

Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia)

The Toyon is a tree in the Rosaceae family. Native Californians used this plant for food, medicine and tool making material. To remove bitterness and astringency, foragers allowed the berries to fully ripen. The ripe berries were then harvested and exposed to heat. This process softened the taste.

Coastal sagebrush

photo: Rachel Cobb

Coastal sagebrush (Artemisia californica)

California sagebrush is a species of North American shrub in the sunflower family (Asteraceae). Although Artemisia californica is a sagebrush, as opposed to a true sage, it can still be used as a spice in cooking, or made into a tea.

The Kumeyaay used this aromatic herb for a number of medicinal applications. They prepared the leaves and stems into an infusion to wash sores and wounds. They also mixed this bitter sagebrush tea with Salvia (sage) for fevers.

Coastal sagebrush was also used by women of the Cahuilla and Tongva cultures to alleviate menstrual cramps and ease labor. Apparently, the plant stimulates the uterine mucosa, thereby quickening childbirth.

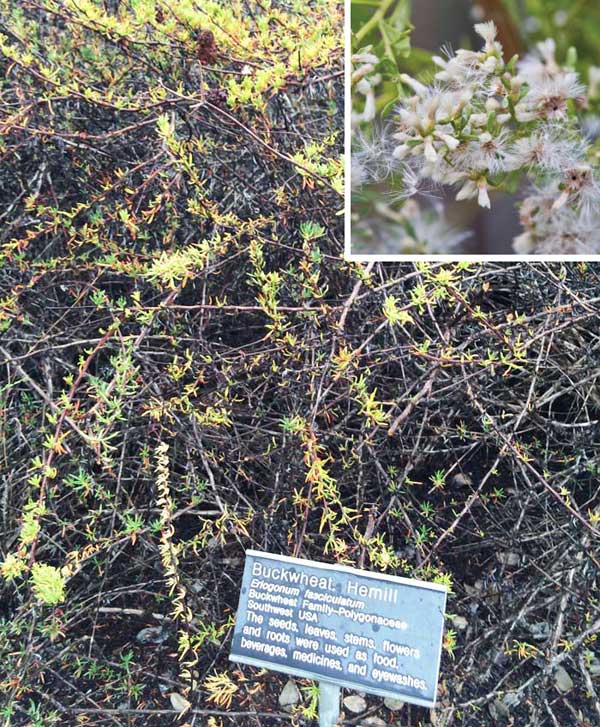

California buckwheat

California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum)

California buckwheat is a common shrub throughout southwestern United States. This plant rows on scrubby slopes and in chaparral habitats. Many southwestern Native American groups used parts of this plant for medicinal uses, including the treatment of headache, diarrhea, and wounds.

The Kumeyaay used both the roots and the flowers to relieve digestive disorders (diarrhea). The fresh roots of the buckwheat were pounded on a metate, then cooked until the roots turned a reddish color.

Lemonade berry

photo: Rachel Cobb

Lemonade berry (Rhus integrifolia)

Despite the inviting name, the berries from this plant are not commonly used to make lemonade flavored drinks. Many plants within the Rhus genus are considered toxic. The family, Anacardiaceae, also contains poison oak and mango. Allergic reactions may result from skin contact with sap from some of the Rhus genus.

An oil can be extracted from lemonade berry seeds; this oil is employed to manufacture bright burning candles.

Orcutt’s goldenbush

Orcutt’s goldenbush (Hazardia orcuttii)

Orcutt’s goldenbush is a rare, small shrub in the Aster family. In late summer it produces small yellow flowers. The only wild population in the U.S. grows a few miles from Encinitas, California, just north of San Elijo Lagoon. Northern Baja also contains a few wild populations.

The conservation status for this daisy is Critically Imperiled.

Jojoba

Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis)

Jojoba is the sole species of the family Simmondsiaceae.

Native Americans first discovered the importance and versatility of jojoba. During the early 18th century, Jesuit missionaries along the Baja coast observed natives heating jojoba seeds, then grinding them with a mortar and pestle to create a buttery paste. The paste was then applied to the skin and hair to heal and condition. The O’odham people of the Sonoran biome treated burns with a similar paste made from the jojoba nut.

Currently, jojoba is grown for the liquid wax held in its seeds. This jojoba oil is rare in that its composed of an extremely long carbon chain (C36–C46), making jojoba oil more similar to whale oil than to traditional vegetable oils. Applications vary from engine lubricating oil to cooking oil.

Kumeyaay hunters ate jojoba seeds on the trail to keep their hunger at bay.

We hope this list provides a glimpse into the way the Kumeyaay culture relied on plants to survive.

To see all these native plants growing in their natural environment, stop by and visit the San Diego Botanic Garden.

Ethnobotanical anecdotes used in this article derive from multiple sources including:

Wilken, Michael Alan. An Ethnobotany of Baja California’s Kumeyaay Indians. Diss. San Diego State University, 2012.

50 Common Edible and Useful Plants of the Southwest, Western National Parks Association, 2009.